No, Technology Isn’t Making Us Stupider: What Psychology Says

Every technological revolution arrives with its prophecy of intellectual decay. They said it about books, then about television, and now about artificial intelligence. The article in El Diario about the supposed golden age of stupidity repeats that old fear in new language. But if we look at the evidence through psychology, the picture is very different.

Technology does change the way we think, yes. It affects attention, reorganizes memory, and encourages a growing dependence on external devices. However, that doesn’t mean we’re becoming less intelligent. The human brain doesn’t shut down when we use digital tools: it reorganizes itself. What science calls cognitive offloading (delegating certain mental tasks to external supports) doesn’t imply loss, but adaptation. Just as we once began writing to free up oral memory, now we externalize data so we can focus on more complex processes. That’s basically why we don’t remember phone numbers anymore.

The real problem appears when we confuse convenience with thought. If we let algorithms decide for us, intelligence doesn’t weaken: it falls asleep. But the culprit isn’t the machine; it’s the user who gives up the mental friction required to understand the world. Social psychology explains this catastrophism as negativity bias: we often overvalue what we lose and ignore what we gain. From the printing press to AI, the fear of cognitive decline is more emotional than scientific.

Today we know that the brain adapts to the digital environment just as it once adapted to written language. We’re not witnessing an intellectual collapse, but a reconfiguration. The challenge isn’t to resist technology, but to learn to use it with critical attention. Thinking remains a voluntary act, even if the world keeps trying to distract us.

We’re not living through a golden age of stupidity. We’re living through an age of cognitive mutation. Intelligence isn’t dying: it’s changing shape. The real danger doesn’t lie in machines that think too much, but in humans who’ve stopped doing so.

Market Polyamory, Patriarchal Monogamy & Other Queer™ Traps

We say we’re freeing ourselves from patriarchal monogamy—but what if we’re just signing a different contract with capitalism? This post dives into open relationships, gay culture, and why care might be the most radical thing left. Are open relationships really liberating, or are we just swapping patriarchy for emotional capitalism? A queer critique of love,… Sigue leyendo →

What is “normativity” and why does it matter

Normativity is a concept that increasingly sparks debate. It’s all about normativity. There’s no more common topic among hipsters (and I say this as someone who’s been around a while) than this. There’s nothing more Instagram-worthy than not being normative. It’s at the heart of a cultural battle in which all of us, in one way or another, are immersed. But what exactly is normativity?

Normativity is the set of social rules and expectations that guide our behaviors. These norms, whether explicit or implicit, tell us how we should behave in different social contexts, how we should be, or what we should look like. Societies generate “normativities” because they regulate our interactions and create a framework that facilitates coexistence. Without this framework, functioning as a community would be difficult, if not impossible.

From a psychological perspective, normativity serves a fundamental purpose: it reduces cognitive load. Instead of constantly analyzing and deciding how to behave in every situation, social norms provide us with a pre-established guide. This way, we can act automatically in many situations, saving mental energy for more complex scenarios. We are biological beings with a much more limited cognitive capacity than we often believe. We’re wired to think as little as possible.

Imagine the following situation: you’re walking down the street, there’s no one around, it’s dark, and you see a person whose features you can’t make out or what they’re doing. What you should do is avoid that person. You can’t stop to observe whether they’re carrying a knife or if they’re watching you. Because if that’s the case, by the time you realize it, they’ll have already attacked you. That’s why we behave in such situations without thinking, without considering all the variables in the environment.

Normativity works in much the same way. To function in society, we can’t process all the information available to us in every situation. We have to know how to react quickly and effectively, at least statistically speaking.

However, while the norms that regulate our social behavior are necessary, normativity is neither a fixed nor a universal entity. It is culturally and historically situated. What is considered normal in one society or era can be seen as completely inappropriate in another, even within the same society. Norms change over time and depend on the culture that sustains them because the circumstances of the environment and the structure of society itself change. This variability makes it clear that there is no one “right” way to do things, even though the society we live in may lead us to think otherwise. That’s why norms vary from one society to another.

Despite its usefulness, normativity can also be a source of suffering for those who don’t fit in. People who don’t conform to physical, ideological, or behavioral norms may experience exclusion or rejection, and that is universal. This can affect individuals based on their physical appearance—whether they’re overweight, very thin, have a visible illness, or a different skin tone—or even how they think or choose to live their lives.

Faced with this discomfort, some people seek to challenge social norms to alleviate their suffering. In the gay community, for example, “bears” have created a subculture that celebrates the natural physical appearance of men who don’t conform to the ideal of youthful, muscular bodies. However, what often happens is that one normativity is simply replaced with another. Instead of eliminating the system, as is often believed, another set of expectations is created that can end up being just as restrictive. That’s why we all know bears who act like divas. And by the way, calling them “divas” is just as misogynistic and disgusting as saying someone is “a top” or “a bottom.” Let’s be clear: liking anal sex isn’t wrong, and you can be a “power bottom” in masculine terms. In this, English does a better job; the term “power bottom” is fantastic, I must say.

From a psychological perspective, going back to the topic, perhaps the solution isn’t to destroy norms or replace them with new ones. Perhaps the healthiest path is to accept that we can’t please everyone or meet every expectation. What’s truly important is learning to love ourselves as we are, with our imperfections. It’s not about adapting to norms or creating new ones that better suit us, but rather accepting that we’re fallible and don’t always fit in. As Carl Rogers said, total self-acceptance is key to well-being. Self-acceptance doesn’t mean giving up on improving; it means stopping the fight to fit into imposed molds and learning to value our individuality.

This doesn’t mean we should uphold harmful and rigid norms. On the contrary, we must fight for the acceptance of all people, whether they fit the norm or not. We must strive to ensure that non-normative behavior is not a reason for discrimination or social backlash. By the way, being a serial killer is just as non-normative as being gay, so “having no norms” doesn’t work. Norms are necessary, but as a society, we must ensure they don’t cause suffering, either on an individual or collective level.

Why do languages evolve?

Understanding why languages change is essential to comprehending how human beings communicate, evolve culturally, and adapt to new social and technological realities. Comparative linguistics is a discipline that not only explains and illustrates our past or the contacts between different civilisations, but it also helps us understand how our brain processes, creates, and modifies language.… Sigue leyendo →

On Plagiarism at Schools

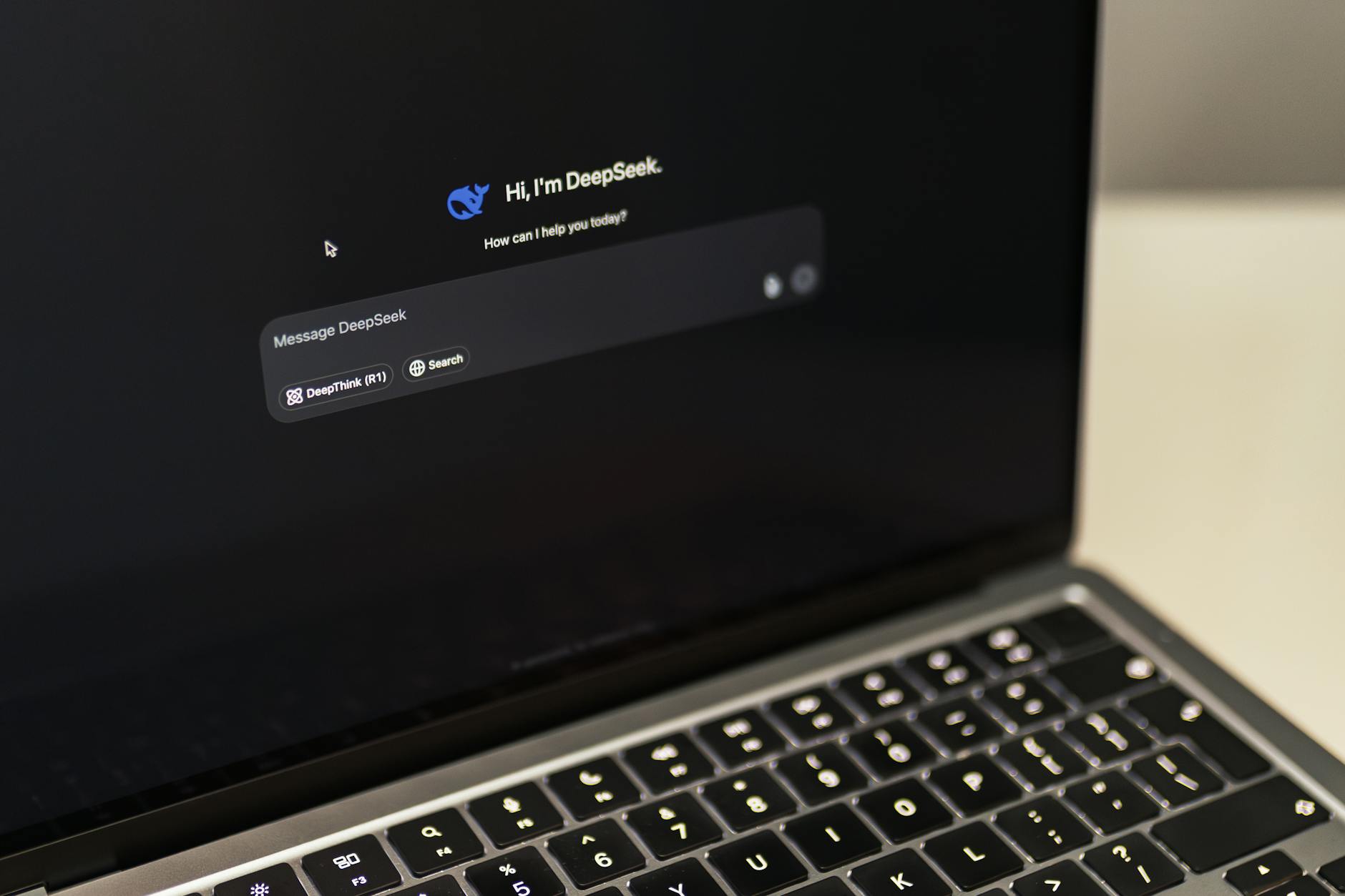

I am reviewing the final projects of my students, and out of 21, 7 have tested positive for plagiarism, and another 5 I suspect have used ChatGPT. We are overwhelmed: we don’t know how to solve the problem that arises from the use of AI in written assignments.

The prevalence of plagiarism among our students has grown exponentially, partly driven by access to advanced technologies like ChatGPT. This tool, designed to facilitate interaction and content generation, has also become a very tempting solution that can encourage dishonest academic practices. Even though you know your student didn’t write that text, because you know their writing style, analytical abilities, and the amount of information they handle, it’s impossible to find indisputable evidence that they used artificial intelligence. Therefore, it’s almost impossible to take administrative measures to address the situation.

The ease with which young people can obtain instant and well-written information through ChatGPT is the key to understand the whole situation: it has never been so easy to write a paper. Additionally, academic pressure and competition among peers can drive some to seek shortcuts to meet expectations and outperform others. The academic pressure exerted by some families is also unbearable, and they end up assuming that they have to excel in all subjects. It’s clear that they make the decision to be dishonest and could choose to make the effort or risk getting a lower grade, but I sincerely believe that we have never placed as much importance on academic results as we do now. It is our responsibility, as educators and families, to alleviate the stress they experience and not add fuel to the fire.

As I mentioned, ChatGPT’s ability to generate original and coherent content blurs the line between authentic and plagiarised work. Plagiarism detection algorithms often struggle to identify subtle similarities in wording, leading to false negatives or positives. And even though you know it sounds like ChatGPT, because you develop a sense for it, it is impossible to prove. I know I am repeating myself, but it is one of the key issues we face. The adaptability of artificial intelligence to generate unique content can confuse conventional detection systems, allowing plagiarism to go unnoticed. These systems are so good that every passing week makes it more difficult to deal with the issue.

Addressing the issue of plagiarism among young people today, in my opinion, requires a comprehensive approach that includes promoting ethical academic practices, understanding the long-term implications of plagiarism, and developing advanced detection technologies that can adapt to the constant evolution of tools like ChatGPT. But above all, we must stop pressuring students to pursue university degrees, preferably dual degrees, with internships, three languages, and a bustling social life.

It’s impossible.

Spanish version here.